French Colonialism

During the period of French colonialism in Vietnam, drastic large-scale infrastructural and planning changes were forced onto the country.

This colonial urban planning was so severe, it would lay the foundation for numerous socio-economic inequalities that continues to pervade Vietnamese cities today.

Land Dispossession & Displacement

In the beginning French occupation, countless Vietnamese homes were demolished in order to make room for arriving white settlers and tourists. These Vietnamese families were displaced and pushed into projects in segregated neighborhoods, such as Hanoi’s “Thirty-Six Streets.”

This was pursued so that the French could import grid-like planning to the city, drawing out wider streets and pathways. It was also easier for the French to militarily occupy, patrol, and surveil cities in Vietnam.

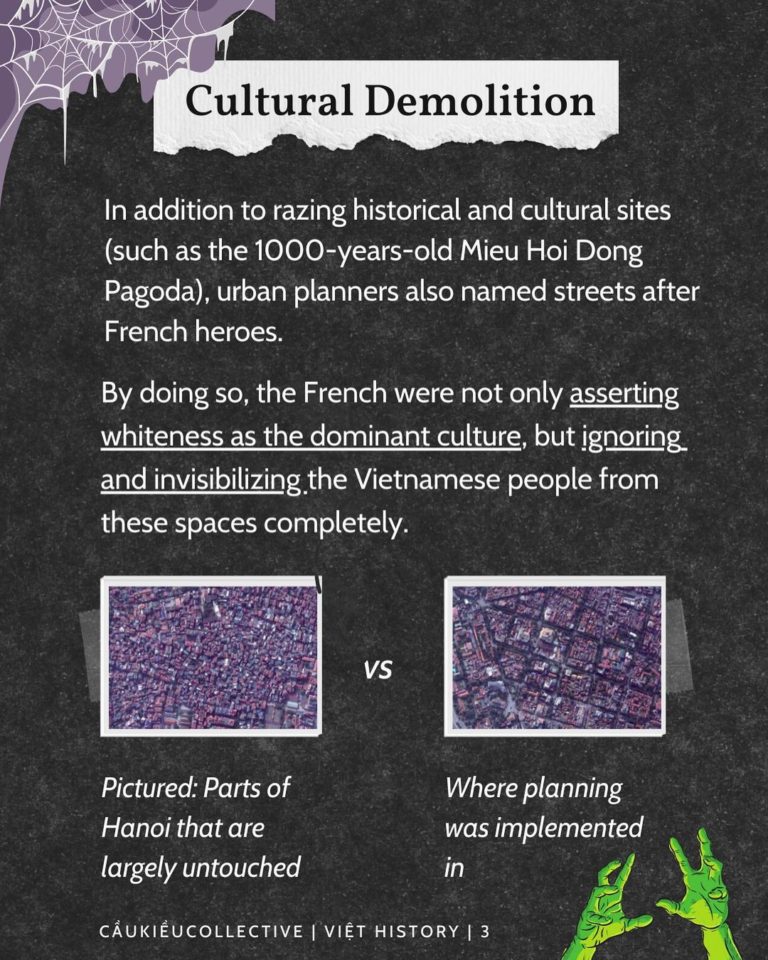

Cultural Demolition

In addition to razing historical and cultural sites (such as the 1000-years-old Mieu Hoi Dong Pagoda), urban planners also named streets after French heroes.

By doing so, the French were not only asserting whiteness as the dominant culture, but ignoring and invisibilizing the Vietnamese people from these spaces completely.

Pictures in gallery below: Parts of Hanoi that are largely untouched vs. where planning was implemented in

Colonial Conditions

Due to mass evictions and displacement, Vietnamese neighborhoods were dense, cramped and dark, making them more prone to disease.

In contrast, French district planning intentionally incorporated large amounts of vast spaces and sprawl, surrounding villas with private parks, lawns, gardens, and hunting grounds.

An example of this is the Hanoi Sewage system. Although the French earned praise and awe for their innovation, the system filled native quarters with human waste during rain.

Intentionally Imperfect Urban Apartheid

The French never made up more than 5% of Hanoi’s population, yet living on a third of the city’s land.

Despite the segregation, the French deliberately chose to make the districts infrastructurally permeable so that Vietnamese people would be able to be exploited for cheap labor in the French District.

This socio-economic order was centered and built around race, as even poor non-French whites were appointed to be overseers of Vietnamese laborers.

Orientalism/ Aesthetics/ Tourism

The planners’ dream was for Saigon to be the “Paris of Indochina”, while Hanoi was to be its “Versailles”, envisioning these 2 cities as embodiments of distinct French characteristics against an “oriental” backdrop.

Meanwhile, Vietnamese people would be forced to get rid of their wooden huts and grass shacks, which French saw as a blemish on the aesthetic.

This serves for the benefit of white tourists and longer-term settlers in Vietnam, who could experience tidbits of “exoticism” in the comfort of western-styled infrastructure.

Rebuilding efforts

Since Vietnam reclaimed self-determination over its land and people, the country has made efforts to reduce these inequalities, including:

- Uplifting its citizens out of poverty and illiteracy through urbanization projects.

- Preserving cultures and rebuilding historical sites destroyed by the French.

Nation Building

Even after defeating the French, Vietnam’s urban environments remained shaped by apartheid and continue to perpetuate socio-economic inequalities between residents.

Conclusion

While Vietnam has historically only been seen as a site of profit or commodification for the West, now under Vietnamese agency, urban planning can be utilized for the welfare of the people.

Questions to Consider:

Sources

Building Colonial Whiteness on the Red River. Race, Power, and Urbanism in Paul Doumer’s Hanoi, 1897-1902 by Michael G Vann

Tradition in the Service of Modernity: Architecture and Urbanism in French Colonial Policy, 1900-1930 by Gwendolyn Wright

Vocabularies of Spatiality in French Colonial Urbanism: Some Covert Rationales of Street Names in Colonial Dakar, West Africa and Saigon, Indochina by Ambe J. Njoh and Esther P. Chie