Everyday, there is a growing awareness that capitalism is a major cause for societal inequality and mass suffering. As climate change, lack of access to healthcare, and poverty continue to worsen, the top 20 U.S. billionaires have gotten $941 billion richer in the last 20 months.

Meanwhile, 54% of U.S. adults (125 million) continue to live paycheck-to-paycheck, 21% of which struggle to pay their bills. For millennials, that figure is 70%. In early 2020 in the U.S., the biggest economy in the world, two out of five U.S. adults did not have adequate health insurance.

Because of these and other reasons, there is a growing unease and dissatisfaction with capitalism as the economic system that currently governs our lives.

But what is capitalism exactly? And how does it function?

To unpack it, we continue our series of capitalism 101.

If you haven’t, please check out our first post, What is Capitalism?, where we define “capital”, its inherent need for expansion, and why the primary goal of goods and services under capitalism is to increase profit, not for human needs.

We will continue to go deeper into details of the components that make capitalism a system. In this post, we will look at what makes something a commodity. Understanding this will help us examine the mechanism of capitalism.

What is Commodity?

A commodity is a product or service produced by human labor that is either sold or traded because it is useful and meets a human need or desire.

For example, a cookie can be a commodity because:

It meets a human need or desire, so it has a usefulness. In this case the usefulness of a cookie is based on its taste, its shape, its texture, etc. In other words, the cookie has a use value.

It has to be made, so it has a value associated with the time someone spent making it.

If you buy it, it has a cost. If you trade it for something else, it has an equivalence in its exchange value.

If you work to make a product or provide a service, your labor power, too, is considered a commodity. It has an intrinsic value (use value). It includes an aggregate of your mental, emotional, physical capabilities, your skills, talent, experience, and education – everything it takes for you to produce the product or service. It is w, which you agree to in exchange for a set amount of your time.

This is different from labor, which is something you still do even if you did not get paid to do, and even if no one else found any value in it. For example, spending time writing fanfics, drawing, or gardening.

Commodity in relations to capitalism

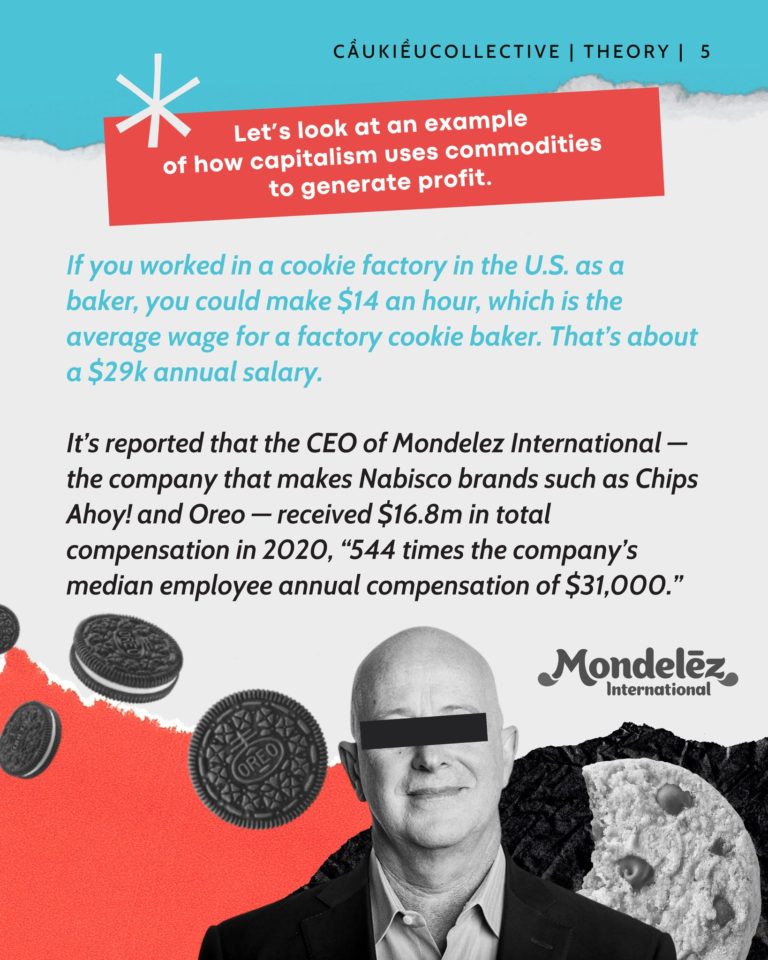

Let’s look at an example of how capitalism uses commodities to generate profit.

If you worked in a cookie factory in the U.S. as a baker, you could make $14 an hour, which is the average wage for a factory cookie baker. That’s about a $29k annual salary. It’s reported that the CEO of Mondelez International — the company that makes Nabisco brands such as Chips Ahoy! and Oreo — received $16.8m in total compensation in 2020, “544 times the company’s median employee annual compensation of $31,000.”

Mondelez International Inc. reported a gross profit of $10.45 billion in 2020 at a gross margin of 40%. With 79,000 employees, this means that the company can pay upward of $130k usd per employee. However, its operating income was $3,853 billion. which includes employee wages. With locations in 42 countries, this surely means that a cookie factory packer in countries outside of the US are getting paid even less than those in the U.S.

Why is there such a huge discrepancy in how much the workers make, the CEO makes, and the profit margin that the company retains?

In the previous section, we established that a commodity is a thing that is: produced by human power, meets a human needs, whether it be a product or service, and is bought, sold, or exchanged. The exchange value is the sales price of the thing. For example, when you make a batch of cookies and sell them, the price you set is the exchange value.

If you were to make the cookies to only meet a human need, you would charge a price that would cover the cost of the ingredients, the time you spent, and the equipment you used. You might also want to make a little profit, so you set the price a little higher. The difference between the price you set and the cost to to produce the cookies is the profit margin.

Under capitalism, corporations want to create a profit margin as large as possible, and as this is the primary goal, they will reduce costs as much as possible, one of which is paying workers.

As a worker, you might mix the batter, bake the cookies, or package them to produce the final product that ends up on the shelves at the store. However, you do not see any of the profit that the company makes.

This process of using commodities to maximize profits, keeping the profit and not sharing it but instead use it to make even more profit is called capital accumulation, which is a cornerstone of capitalism. We’ll continue to explore that more next time in our What is Capitalism? series.

Here are some questions to help you gauge your understanding from reading the article:

- Why is every product under capitalism considered a commodity, including human labor?

- Why is air essential to humans, but it is not considered a commodity?

- What is the difference between use value and exchange value?

- Why is it that if you make a batch of cookies to share, those cookies are not considered a commodity, but a package of cookies in the store is a commodity?

- Why would grocery stores in a capitalist economy destroy food instead of giving it away?

- Why is the commodification of things considered a basic component of capitalism as a system?

Sources

Led By Elon Musk’s Crazy Gains, American Billionaires Have Added Nearly $2 Trillion To Their Fortunes During The Pandemic by Chase Peterson-Withorn

Reality Check: The Paycheck-to-Paycheck Report: June 2021 by PYMNTS.com

Cookie Baker Salaries by Glassdoor

U.S. Health Insurance Coverage in 2020: A Looming Crisis in Affordability by The Commonwealth Fund

‘We’re peons to them’: Nabisco factory workers on why they’re striking by Michael Sainato

Mondelēz International Reports Q4 and FY 2020 Results by Mondelēz International